Early equity: why seed-stage funds outperform later-stage venture

Seed-stage venture capital funds consistently deliver superior returns to their later-stage counterparts.

The reason isn't just timing. It's structural: earlier entry points, higher ownership, and the ability to double down on winners create return profiles that larger, later-stage funds struggle to match.

Across market cycles and geographies, seed-stage venture funds have quietly outperformed - returning >8% higher annually than funds investing later in the startup lifecycle.

Over the last 30 years, Cambridge Associates reports average annual returns of 21.3% for early-stage funds, compared to 12.6% for late-stage.

Yet the majority of investor capital – especially institutional – continues to flow toward late-stage investments.

This imbalance isn’t a quirk of the system – it’s a structural gap that savvy investors can exploit.

Early-stage investors buy in when valuations are low and upside is highest. It's a simple equation: the earlier the entry, the greater the multiple on exit.

Consider two investors in the same company. The seed investor buys in at a $3 million valuation. The Series B investor enters at $50 million. If the company exits at $300 million, the seed investor achieves a 100x return. The Series B investor earns just 6x.

This isn't theoretical. Canva, one of Australia's most successful tech companies, raised its earliest rounds below $40 million. Those early investors realised extraordinary returns – long before most investors could access the opportunity.

The majority of a startup’s value creation happens in its first few years.

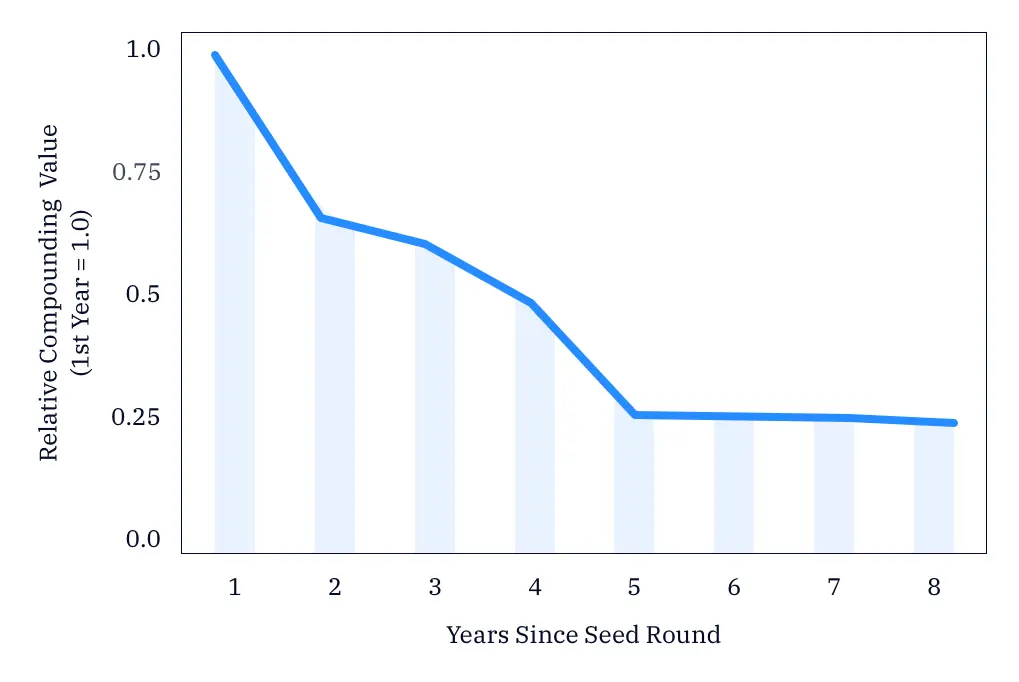

As the data below shows, growth drops off sharply after year one and continues to taper from there. By the time a company raises a Series A, much of the compounding has already taken place.

You can see this in real terms. Going from $100,000 to $1 million in revenue is a 10x leap. That same company, growing from $10 million to $20 million, delivers just 2x, even though the absolute gain is larger.

Seed-stage investors are positioned to capture this early acceleration, when growth is fastest and there is more time for returns to compound. And because seed cheques are smaller, investors can back a broader set of companies early and then concentrate capital where the results justify it.

This dynamic works even better when the fund size is designed to support it.

Seed investors aren't locked into a single decision. Through pro-rata rights and structured follow-on investing, they can double down on winners and let underperformers dilute.

This creates a portfolio model where optionality matters as much as selection. A fund might invest $100,000 in a pre-seed round, then $150,000 six months later, and another $200,000 after product-market fit is established. Each round benefits from deeper insight, stronger alignment, and more conviction.

Later-stage funds typically make large, binary bets. They arrive once risk has shifted from zero to one – but also after much of the value creation has occurred.

Yes, seed-stage portfolios include more failures. But that's the point.

Venture capital operates on power law dynamics. In a well-constructed portfolio, two or three companies will drive the majority of returns. The rest provide exposure in case they break out, not because each one is expected to succeed.

This asymmetry is what enables 20-30% fund-level IRRs over a decade. The key is structure, not perfection – which becomes clearer when you understand how venture returns really work.

The imbalance is even starker here.

Only 7% of Australian VC funding goes to seed-stage companies, according to the 2024 State of Australian Startup Funding report. Yet this is where the most outsized returns are generated - particularly as local companies tap into international markets and trigger valuation re-ratings.

Seed investors can access this arbitrage. Later-stage funds often arrive after it's priced in.

Despite the superior performance of early-stage funds, most institutional capital still flows to later stages.

Institutions tend to favour growth-stage funds because they can deploy larger amounts of capital, show more immediate traction, and offer shorter paths to exit. Seed funds, by contrast, require a longer time horizon, and a broader portfolio approach - harder to scale and justify within traditional fund mandates.

But for investors who can embrace that structure, the upside is clearer than ever.

Add to that the tax efficiency of ESVCLP structures and a growing volume of global capital entering at Series B and beyond, and the local opportunity becomes clear: the seed stage isn't just high-upside - it's high-leverage.

Early-stage funds have shown greater resilience and performance through market cycles compared to late-stage funds. When the market cools, seed gets even stronger.

Unlike growth-stage companies, early-stage startups aren't under pressure to show profitability or defend inflated valuations. They build in the shadows, often at more attractive prices.

Historically, funds raised during downturns outperform. Investors willing to enter at seed during these periods often capture companies at their most undervalued - and participate in their full lifecycle of growth.

For investors allocating to venture capital, stage matters as much as manager.

Seed-stage funds offer:

This is not a strategy for every investor. It requires patience, comfort with volatility, and belief in the long game. But for those willing to lean in, the numbers - and the results - are hard to ignore.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice or an offer to invest. Investments in venture capital carry significant risks and are suitable only for sophisticated investors. For more information, please request our Information Memorandum. This offer is not available to retail investors.